By: Karthigeyan Ganesh Shankar & Srividya Prasad

Ever notice how we can stroll from the factory floor to the IT desk without whipping out Google Maps for every ten steps we take? Our brain quietly stitches together landmarks, memories, and a pinch of intuition, guiding us on autopilot to our destination. That’s muscle memory at work on home turf, our brain parses through a well-rehearsed routine.

Now imagine giving that same “street-smart” superpower to an industrial robot. That is exactly what we have been tinkering with, teaching our bots to read the factory floor plan the way humans do, so they move to their destinations without having to clutch a digital compass.

The idea of Foundational models is the grain-bound ability to be able to emulate this behaviour for a bot. Given that the bot is navigating a known environment (or unseen environment), would it be able to move to a destination with reasonable control and precision?

Recently, there has been a lot of activity around LLMs (Large Language models) and the more advanced VLMs (Vision Language models) which have been trained by ingesting large amounts of data and providing reasonably good predictions. Intuition says we can train robots to recognize aisles, pallets, and loading bays the same way we spot the coffee machine on a Monday morning fast, natural, and with zero second-guesses!

The idea is simple: Can we apply the approach of transformers and training on large datasets that made large language models successful, in robotics? Instead of separate algorithms for mapping, localization, and path planning, imagine an end-to-end model that learns navigation from robot datasets and generalizes to new, unseen environments.

This vision is compelling, but the challenges are immense. Unlike text, robotic navigation must account for diverse environments, sensor input data types, intrinsic parameters, actuators, physical dimensions, locomotion types, and degrees of freedom. The data is very multimodal. There’s a lot of research on this and all of us work towards and await the day that these models are ready for real-world deployment, right out-of-the-box.

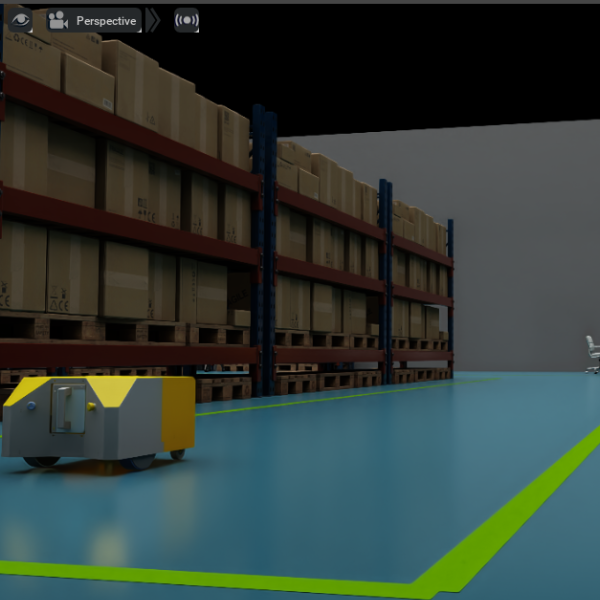

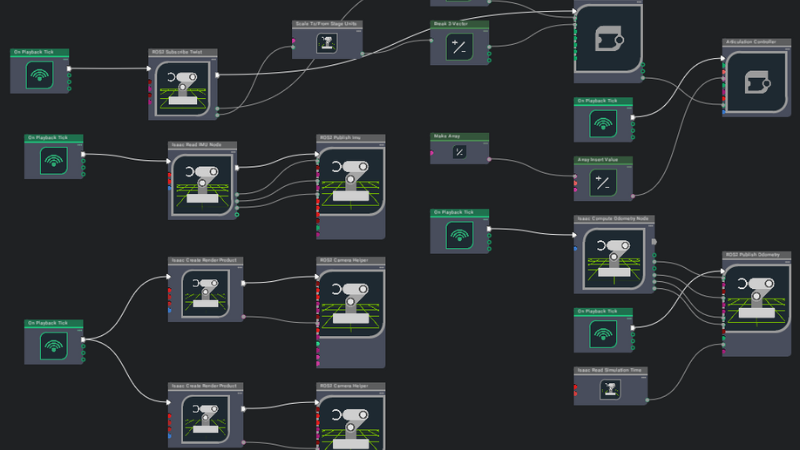

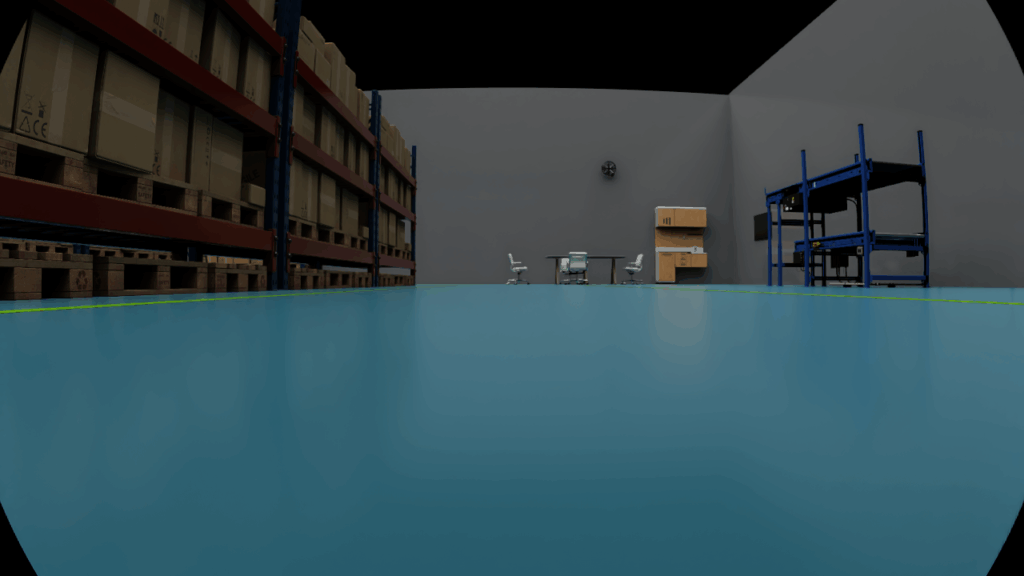

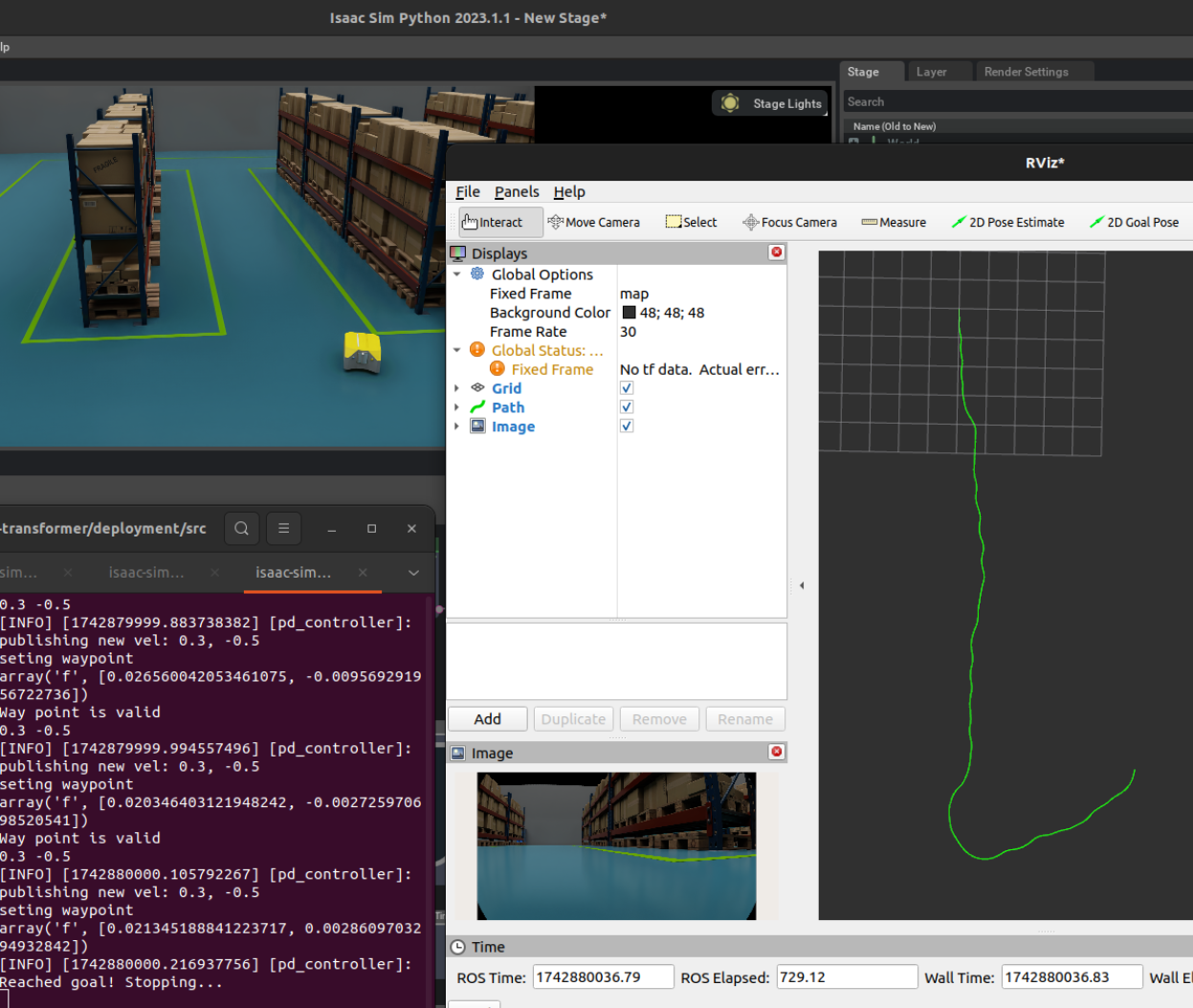

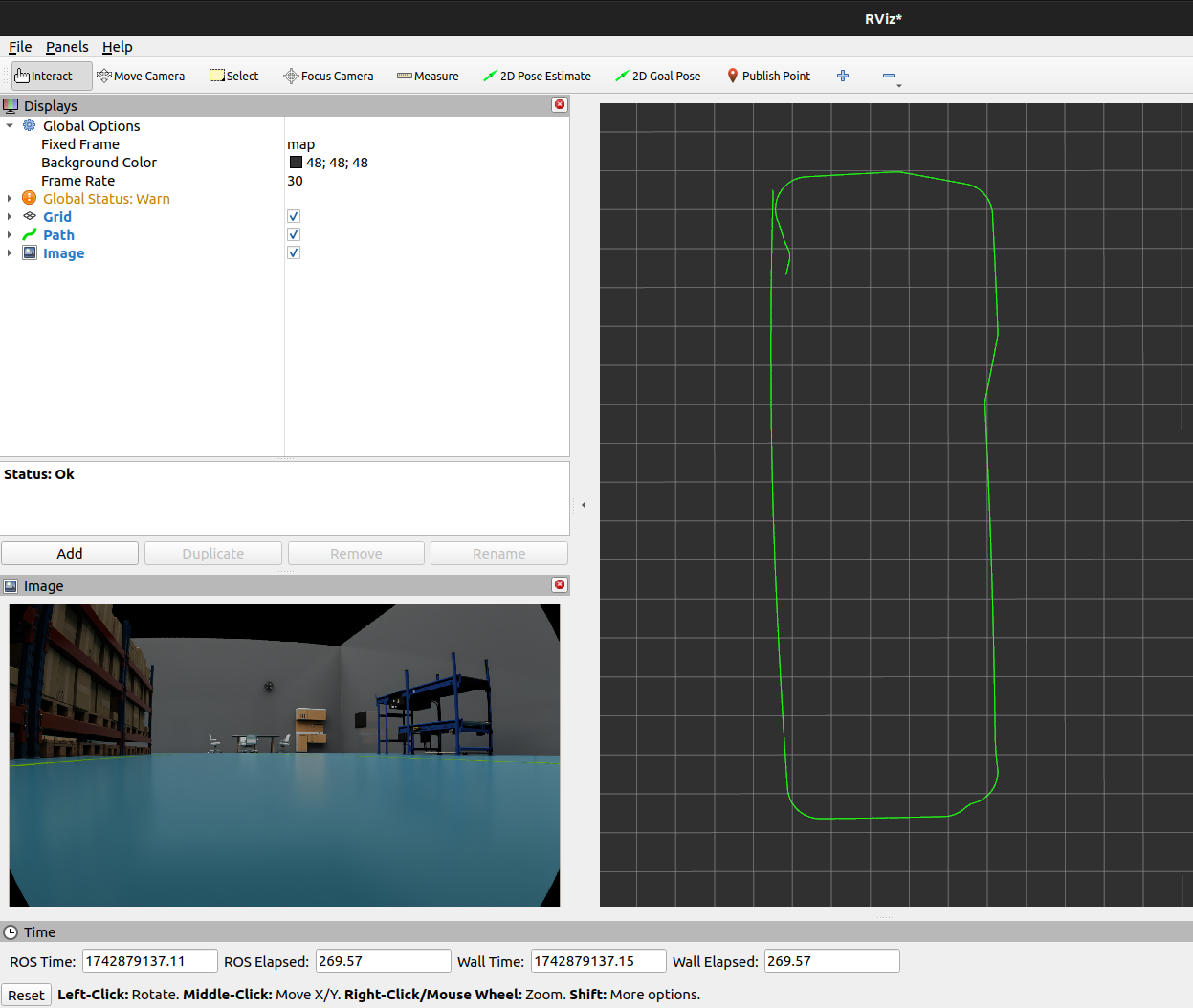

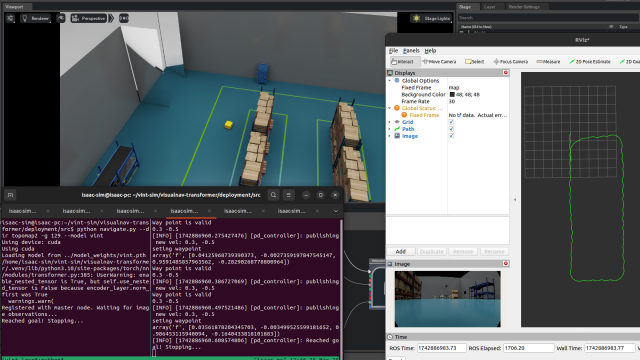

We took this idea forward with two promising foundation models on our Sherpa-RP, a mobile robot platform designed, equipped with sensors and motors and engineered by Ati Motors for research purposes. We adopted a simulation-first approach in order to test and fine tune the two models on Nvidia’s Isaac Sim environment.

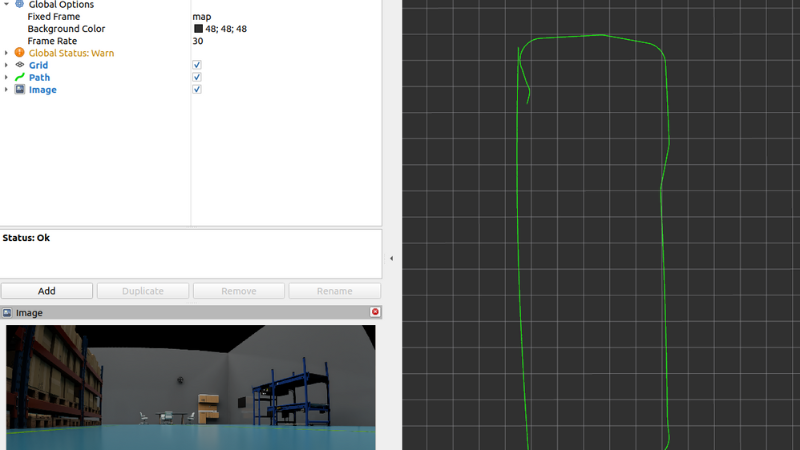

ViNT (Visual Navigation Transformer) creates a topological map by teleoperating the robot, then uses transformer-attention to navigate between nodes by generating waypoints.

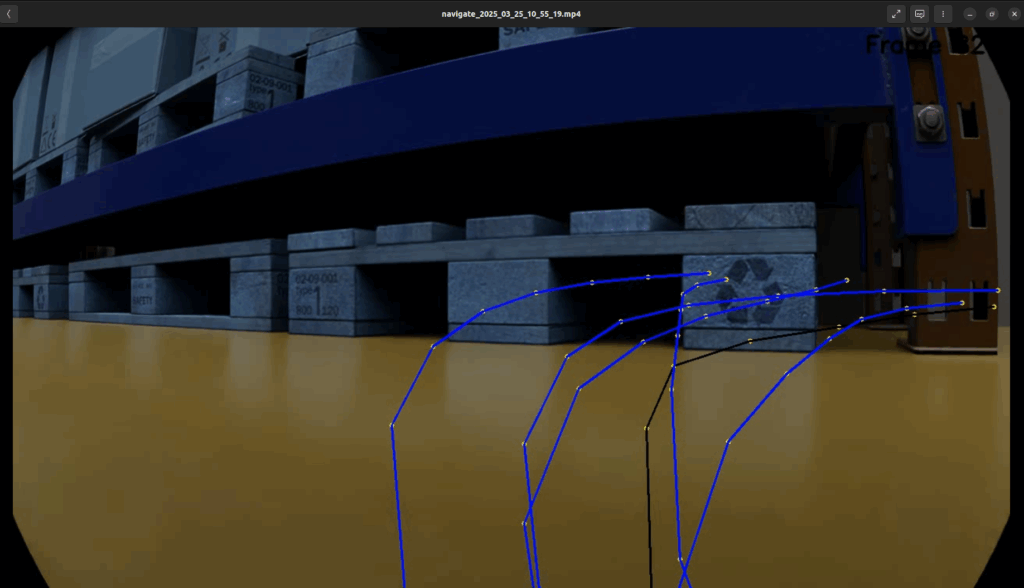

Whereas NoMaD (Navigation with Goal Masked Diffusion) uses diffusion models to predict actions from random noise based on visual understanding from training data.

The table below summarizes our key observations with the two foundational models we studied on our platform

- Majorly successful goal-reaching runs with excellent repeatability

- Reliable within mapped environments

- It did not avoid dynamic obstacles like humans walking into its path

- It was about to collide into chairs, glass walls

- Took unnecessarily long paths when short paths existed in the map

- More likely to be successful when the goal image has a distinguishable object

|

Key Insights:

- Domain-Specific Learning is Critical

NoMaD’s affordances failed in our virtual warehouse. While the trained model could have learnt to avoid office halls or not go off the road outdoors from training data, it did not recognize that warehouse rack undersides are non-navigable. Foundation models are not truly foundational until they are trained in the domain of interest. We must finetune the model instead of relying on zero-shot navigation.

- Robot Embodiment Matters

Both models struggled with spatial reasoning that depends on physical robot dimensions. Without explicit embodiment knowledge, they misjudge available space. Accurate geometry awareness is essential for reliable operation. - Safety Must Be Prioritized

Despite claims of emergent avoidance, we saw inadequate safety behaviors. In industrial or service settings, the robot must detect and avoid dynamic obstacles or replan around static ones. Such mechanisms cannot be compromised.

- System Optimization

The navigation runs at 4 Hz and the control loop at 10 Hz. The model needs GPU compute to meet this timing. Profiling showed time lost in input data formatting. We need smaller, optimized models for edge deployment. - Smarter Spatial Awareness and Path Planning

If the robot gets lost, there is no feedback to recover. A robot cannot be localized without prior node knowledge. While it follows sequences well, we still do not know what defines them. Models are to be extended to plan across the full topomap, not just between adjacent nodes.

- Smoother motion

Traditional path planning produces smooth, optimal trajectories. Both ViNT and NoMaD generated noisy actions with unnecessary angular velocity variations, even for straightforward goals. Using a better tracker to ensure we reach the waypoint could also help mitigate this.

Recent Research:

Several more recent approaches attempt to address the current limitations in robot navigation. One promising direction is using models like NaviDiffuser, which generate entire action sequences instead of just single-step actions. This enables longer-term planning that considers multiple objectives such as safety, efficiency, and operational cost.

To improve obstacle avoidance, the CARE framework enhances navigation by combining ViNT with depth estimation and a local costmap, changing trajectories to replan around obstacles or immediately avoid them.

Recent work like NaviBridger holds promise for smoother and smarter actions by denoising previous actions rather than denoising random actions from scratch for each frame.

Safety is also being tackled through hybrid approaches like Risk-Guided Diffusion, which fuses a fast, learned policy with a slower, physics-based controller. This balances the adaptability of foundational models with the reliability of formal safety guarantees.

In service-oriented scenarios, object-based navigation like LM-Nav leverages visual language models to identify landmarks in images, constructing a navigation graph and planning paths to specific goals. While not ideal for repetitive warehouse automation, this technique offers significant value in object-rich environments.

Another innovative approach is LLM-guided planning, where large language models use their commonly known knowledge of the world to inform navigation. This semantic understanding acts as a powerful heuristic, enabling more intelligent and context-aware decision-making.

Future Directions

Testing ViNT and NoMaD on the Sherpa-RP, our mobile robot platform for autonomy research, showed us both the potential and current limitations. They helped us understand what are the needs that have to be addressed for real world applications and how they are being solved or thought about in the latest research publications.

We are actively researching

- Hybrid approaches supplementing the explored models with active feedback

- Generating synthetic warehouse training data for finetuning these models

- Multi-modal models with depth and IMU fusion

The future does lie in thoughtful combinations of traditional and learned models utilising the strengths of both. As researchers continue pushing boundaries and addressing current limitations, we are optimistic about the eventual realization of truly general robotic navigation systems.

References

- ViNT: A Foundation Model for Visual Navigation – https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.14846

- NoMaD: Goal Masked Diffusion Policies for Navigation and Exploration –

https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.07896 - NaviDiffuser: Cost‑Guided Diffusion Model for Visual Navigation –

https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.10003 - CARE: Enhancing Safety of Foundation Models for Visual Navigation through Collision Avoidance via Repulsive Estimation – https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.03834

- NaviBridger: Prior Does Matter – Visual Navigation via Denoising Diffusion Bridge Models – https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.10041

- Risk-Guided Diffusion: Toward Deploying Robot Foundation Models In Space, Where Failure Is Not An Option – https://arxiv.org/pdf/2506.17601

- LM-Nav: Robotic Navigation with Large Pre-Trained Models of Language, Vision, and Action – https://arxiv.org/abs/2207.04429

- Navigation with Large Language Models: Semantic Guesswork as a Heuristic for Planning – https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.10103

Back To Blogs

Back To Blogs